The art of the Mordovian sculptor Stepan Nefedov, inspired by the name of his native people - Erzia - can rightfully be considered one of the most amazing pages in the world art of the 20th century.

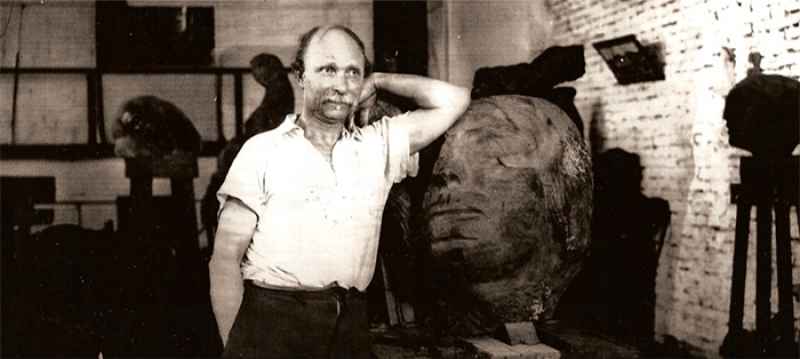

Stepan Dmitrievich Nefedov (Erzia) was born on October 27 (November 8), 1876, in the village of Baev in the Alatyr district of the Simbirsk province in a peasant family. He studied sculpture at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture in the workshop of S. Volnukhin.

In the spring of 1907, Erzia came to Italy. Traveling to ancient cities, and visiting famous museums and galleries, he became acquainted with antique sculpture, and the art of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, immersing himself in the world’s artistic heritage. He lived and worked at Villa Daniele Tinelli in Lago Maggiore, later in Milan, and visited Rome, Venice, and Florence. In 1909, the young sculptor made his debut at the International Art Exhibition in Venice, which brought him his first real success. The Italian press wrote enthusiastically about him, and he was warmly supported by the European art specialist Hugo Nebbia.

From the end of 1909 to 1913, Erzia lived and worked in Nice, Paris, and Seaux, actively participating in prestigious exhibitions in France and Germany, the Rome International Exhibition in 1911, traveling around Europe, and visiting Switzerland and London. From the end of 1913, he returned to Italy, living in Levanto and Carrara, where he successfully worked with marble. In Carrara, Garibaldi’s pension still exists, where the Russian sculptor lived in 1914. He also often visited the dacha of the Russian emigrant writer A. Amfiteatrov in Fecchano, where he made a statue of John the Baptist for the local church of Cristo Re on order. He was preparing to participate in the Venice International Exhibition with his work “Agrippina.”

In the revolutionary years in the Urals and later in the Caucasus, where the sculptor spent several extremely fruitful years of his life, Erzia’s gift for monumentalism, marked in his Italian period of creativity, was brightly revealed. He wrote his own interesting chapter in Lenin’s plan of monumental propaganda, proving that he could be absolutely consonant with the modern era.

Waking up one morning after a restless night, Gregor Samsa found himself in his bed transformed into a monstrous insect.

The creative method of the young sculptor, so successfully developed by him in Europe and Russia, based on bright individuality, skill, and amazing productivity, flourished in Argentina (1927-1950).

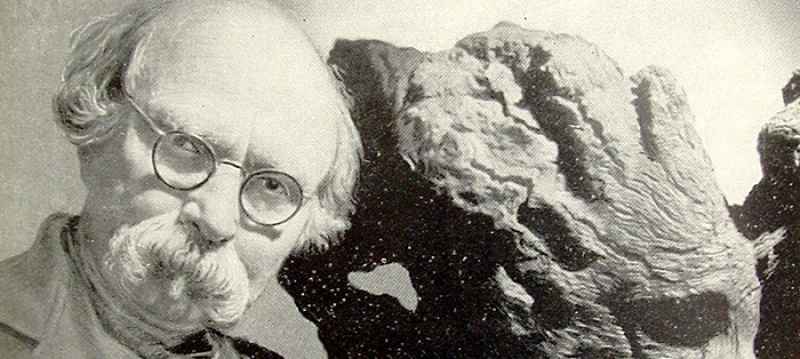

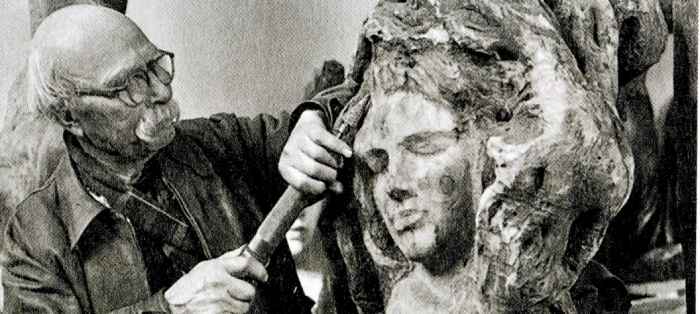

It was in Argentina that the sculptor discovered the subtropical quebracho tree – extremely hard, with an expressive pattern, a wide range of color shades, and picturesque growths that determined the features of Erzia’s new manner. The decorative effect was enhanced by the contrast of untreated wood with carefully polished surfaces.

During twenty-three years of his stay in this fantastic country, the sculptor created works, many of which should rightfully be included in the treasury of world art of the 20th century. Every year, Erzia participated in exhibitions in Argentina, often organizing personal exhibitions. Many works created during the Argentine period can rightfully be included in the history of world sculpture of the 20th century. These include “Leo Tolstoy,” “Beethoven,” “Moses,” “Grieg’s Music,” “Portrait of Secretary Rambindtranat Tagore,” “Inca’s Daughter,” “Medusa,” “Melpomene,” “Wave,” “Chilean Woman,” and “Nude.” The work of the Russian sculptor has always been at the center of the attention of journalists and artists, causing unwavering interest and admiration from numerous fans. Bold experiments with wood, trips to the jungle, grandiose monumental designs, the life of a hermit artist, friendship with great contemporaries – all these are pages of the long fantastic life of the Russian sculptor in South America.

But despite Erzia’s well-known reputation abroad, few remembered him in his homeland, which the aging sculptor constantly thought about. For a long time living abroad and in solitude, he rightly worried about the fate of his works.

Stepan Erzia returned to the Soviet Union in 1950. He managed to preserve and bring his works to his native land – the result of many years of intense work, sometimes unbearably heavy, but always joyful. And in his last – Moscow workshop, the sculptor continued to work tirelessly, afraid to put down his chisel even for a moment, because art had always remained the only meaning of his entire life.

Stepan Erzia died in 1959 in Moscow in his workshop and was buried in Mordovia, forever uniting his ashes with his native land. But the art of this amazing sculptor, which knows no boundaries, now belongs to all humanity.

E.V. Butrova